A seemingly random memory has been haunting me these past weeks, calling to be written, so here it goes:

Shortly after my mother’s death, I flew to New York to visit my dad. He picked me up at the White Plains airport, as he always did, but for the first time we didn’t have my mother to return to. Instead he’d brought take-out sushi and we drove to a city park that was new to me. Afterward we would go directly to a Transplant Support Organization meeting in Rye, a group my father helped found and where he was much loved, to watch a documentary about a lesbian couple. I can’t remember which organ one of them needed and the other contributed. The movie was good, the gathering wonderfully diverse—some waiting on transplants; some, like my father, long-time recipients; all ages and races and income brackets, all cheering on generosity and life. I felt proud of my dad and grateful to have met his friends.

But it’s that ordinary dinner on the park bench that sticks with me. The grass was mowed. A pond had been artificially carved into the landscape; a Hallmark bridge crossed a narrow stretch. The willow trees caught the evening light. We sat side by side, eating with chopsticks, catching up. We didn’t say anything significant, at least not that I remember. But everything—the curved sidewalk, the pickled ginger, the phenomenon of being alone together—vibrated with newness. My mother was no longer alive. Her absence infused everything with tenderness. We ached for her; we took our first steps into life without her.

Why does this memory return today? This question is endlessly fruitful for those of us who seek the meaning buried in experience. I ask it whenever a memory won’t let me go. My father died in July, and this simple meal on a park bench conjures completely all he meant to me: Our mutual effort to begin again. Our affection for one another. Our delight in the out-of-doors. Our love for, and history with, Japanese food—my parents lived in Tokyo for four years. Our anticipation of sharing more about ourselves than we’d done previously. Our willingness to be awkward in the process.

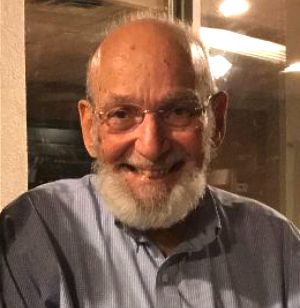

Or maybe the memory returns to me because he’s the one who’s absent now and I’m alone, learning to live without him. His body on that park bench in my memory—chinos, plaid button-down shirt, a new beard we both knew my mother would have disapproved of—is as close as I’ll come now to his physical presence. I press it tight against my chest. This is how the dead continue.

–Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew